Bladder wall thickening and nodular lesions represent findings often encountered during imaging studies – typically cystoscopy or CT scans – prompting investigation into potential underlying causes. These observations don’t necessarily indicate cancer; in fact, they are frequently linked to non-malignant conditions like chronic inflammation, infection, or previous surgical interventions. However, due to the association with bladder cancer, a thorough evaluation is crucial to accurately diagnose and manage these findings. Understanding the nuances of these presentations – what they look like on imaging, potential causes, and necessary follow-up steps – is paramount for both patients experiencing symptoms and healthcare professionals interpreting diagnostic results.

The presence of thickening or nodules within the bladder wall raises concerns because it deviates from the normal smooth contours expected in a healthy bladder. The bladder’s natural structure comprises several layers: the mucosa (innermost), submucosa, muscularis, and serosa/adventitia. Changes to this architecture, particularly alterations in thickness or the appearance of discrete nodules, can signal disruptions caused by various factors. These findings necessitate careful consideration as they could indicate anything from benign reactive changes to more serious pathologies requiring intervention. This article will delve into the specifics of bladder wall thickening and nodular lesions, exploring their potential causes, diagnostic approaches, and appropriate management strategies.

Understanding Bladder Wall Thickening

Bladder wall thickening isn’t a disease in itself, but rather a descriptive finding indicating an alteration in the usual thickness of the bladder layers. Normal bladder wall thickness varies depending on the degree of distension – how full the bladder is during imaging. However, significant and consistent thickening, or disproportionate thickening localized to specific areas, warrants further investigation. Several factors can contribute to this phenomenon:

- Chronic Cystitis: Long-standing inflammation of the bladder, often due to recurrent infections or non-infectious causes like interstitial cystitis, can lead to wall thickening as a result of ongoing repair processes and fibrosis.

- Bladder Outlet Obstruction (BOO): Conditions causing blockage at the bladder neck – such as an enlarged prostate in men or urethral strictures – force the bladder to work harder to empty, leading to muscle hypertrophy and subsequent wall thickening over time.

- Previous Radiation Therapy: Patients who have undergone radiation therapy for pelvic cancers may experience fibrosis and inflammation within the bladder, resulting in a thickened wall even years after treatment completion.

- Long-term Catheterization: Prolonged use of urinary catheters can irritate the bladder lining and cause chronic inflammation leading to thickening.

The degree of thickening isn’t always indicative of severity. Mild diffuse thickening often represents reactive changes or early stages of inflammation, while localized, substantial thickening raises more concern for focal lesions like tumors. It’s important to remember that imaging findings must be interpreted within the clinical context – considering patient symptoms, medical history, and other relevant investigations. Accurate assessment relies on a combination of imaging modalities (CT scans, MRI, cystoscopy) and often requires expert interpretation by a radiologist experienced in uroimaging. A key element in diagnosis is understanding bladder wall irregularity on imaging to distinguish between benign and malignant causes.

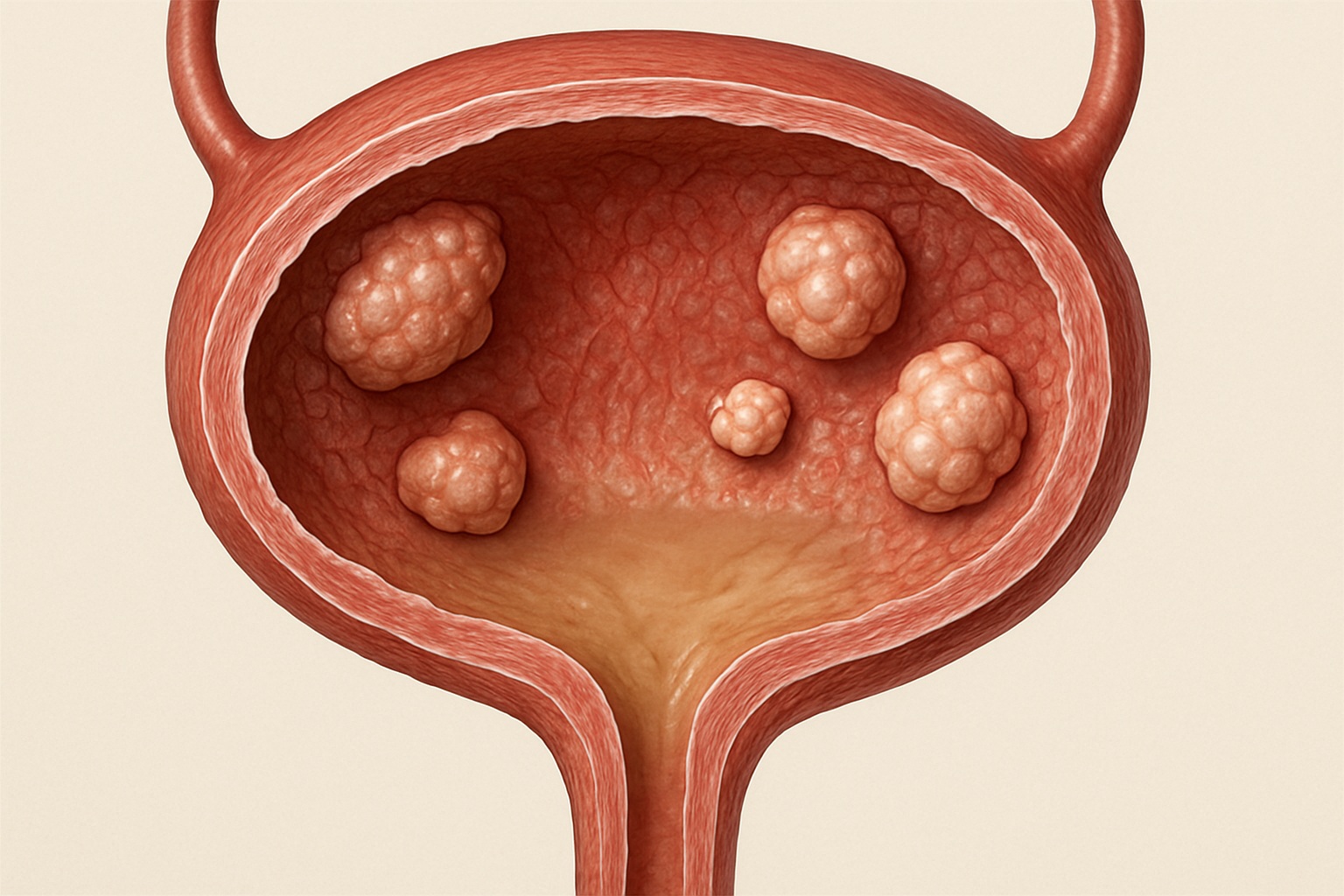

Exploring Bladder Nodular Lesions

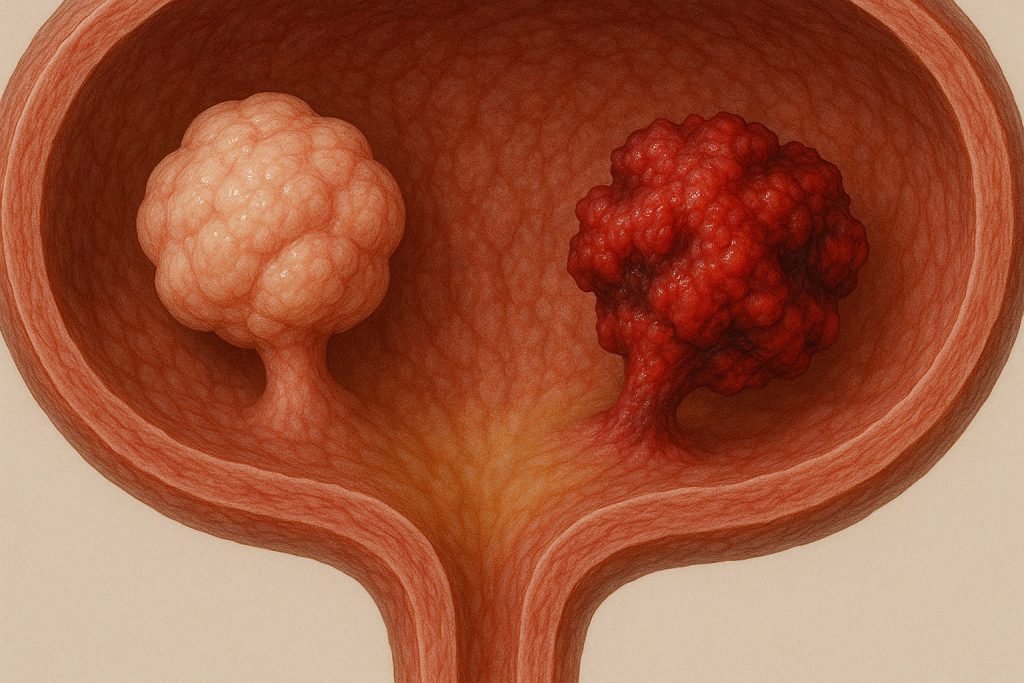

Nodular lesions within the bladder wall refer to discrete masses or bumps protruding from the inner lining. These can range in size, shape, and appearance, influencing the diagnostic approach. While some nodules are benign – like inflammatory pseudopolyps – others may represent early-stage bladder cancer or other malignancies. The primary concern with nodular lesions is differentiating between these possibilities:

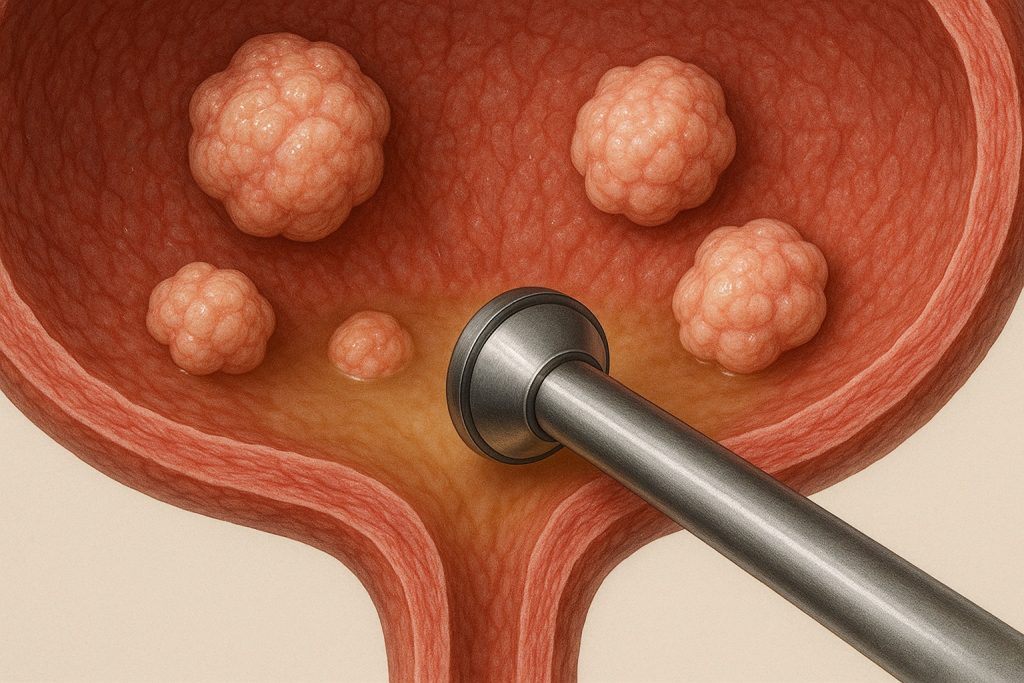

Nodules often appear as focal areas of increased density on CT scans or as distinct masses during cystoscopy (visual examination of the bladder using a small camera). Cystoscopy remains the gold standard for evaluating nodular lesions, allowing direct visualization and biopsy if necessary. The characteristics observed during cystoscopy – such as size, shape, color, and vascularity – provide valuable clues about the nature of the lesion. For example:

- Smooth, symmetrical nodules are more likely to be benign.

- Irregular, asymmetrical nodules with prominent blood vessels raise concern for malignancy.

- Ulcerated or friable (easily bleeding) nodules are highly suspicious for cancer.

The differential diagnosis for bladder nodular lesions is broad and includes – but isn’t limited to – papillary tumors (most commonly urothelial carcinoma), inflammatory pseudopolyps, cystitis glandularis, and rarely, metastatic disease. Careful evaluation and appropriate biopsy are essential for accurate diagnosis and treatment planning. The process of cystoscopic evaluation for bladder wall lesions is often crucial in this determination.

Diagnostic Approaches & Workup

A systematic approach is crucial when evaluating patients with bladder wall thickening or nodular lesions. This typically involves a combination of imaging and potentially invasive procedures:

- Initial Assessment: Begin with a thorough patient history, including symptoms (frequency, urgency, hematuria – blood in the urine, pain), medical history (previous infections, radiation therapy, smoking habits) and family history of bladder cancer. A physical examination is also performed.

- Imaging Studies: CT scans are often the first line imaging modality to assess overall bladder wall thickness and identify any nodular lesions. MRI provides more detailed soft tissue characterization and can help differentiate between benign and malignant nodules. Cystoscopy, as mentioned previously, remains essential for direct visualization and biopsy.

- Biopsy & Histopathology: If a suspicious nodule is identified, a biopsy is usually performed during cystoscopy. The tissue sample is then examined under a microscope by a pathologist to determine the nature of the lesion – whether it’s benign or malignant.

Beyond these core investigations, urine cytology (examining bladder cells for cancerous changes) may be performed, particularly if there’s concern about urothelial carcinoma. In some cases, additional tests like tumor markers or genetic testing might be considered to aid in diagnosis and prognosis. The goal is not simply to identify a thickening or nodule but to accurately characterize its nature and guide appropriate management decisions. Understanding bladder tumor resection and recurrence risk is vital for long term care.

Differentiating Benign from Malignant Lesions

Distinguishing between benign and malignant lesions can be challenging, as some benign conditions can mimic the appearance of cancer. Key features that raise suspicion for malignancy include:

- Rapid Growth: A rapidly enlarging nodule is more likely to be cancerous than a slowly growing one.

- Irregular Shape & Borders: Malignant nodules tend to have irregular shapes and poorly defined borders, while benign lesions are typically smoother and more symmetrical.

- Vascularity: Increased blood flow within the lesion can suggest malignancy.

However, these features aren’t always reliable, hence the importance of histopathological confirmation through biopsy. Inflammatory pseudopolyps, for example, can appear nodular on imaging but represent benign reactive changes due to chronic inflammation. They often resolve with treatment of the underlying inflammatory condition. Conversely, early-stage bladder cancer may present as subtle thickening or small nodules that are difficult to detect without careful cystoscopic examination and biopsy. Smoking and Bladder Cancer Connection is an important consideration for patient history.

Management & Follow-up Considerations

Management strategies depend entirely on the diagnosis established through biopsy. Benign conditions like chronic cystitis typically respond to conservative treatment – antibiotics for infections, pain management for interstitial cystitis, or addressing underlying causes of BOO. Inflammatory pseudopolyps may resolve spontaneously or with anti-inflammatory therapy.

If bladder cancer is diagnosed, treatment options vary depending on the stage and grade of the tumor. These can include:

- Transurethral Resection of Bladder Tumor (TURBT): The most common initial treatment for non-muscle invasive bladder cancer, involving removing the tumor through cystoscopy.

- Intravesical Therapy: Medications instilled directly into the bladder to kill remaining cancer cells after TURBT.

- Radical Cystectomy: Surgical removal of the entire bladder, reserved for more advanced or aggressive tumors.

Regular follow-up is essential even after treatment, including periodic cystoscopies and imaging studies to monitor for recurrence. Patients with a history of bladder cancer are at increased risk of developing new tumors, so ongoing surveillance is critical. A proactive approach to diagnosis and management significantly improves outcomes in patients with bladder wall thickening or nodular lesions, ensuring appropriate care based on the individual’s specific situation. Further surgical options like simultaneous correction of bladder and vaginal prolapse may be needed in some cases.

I had an ultrasound last week that showed bladder wall thickening, but my doctor didn’t explain much. Should I be worried about cancer, or can it be something less serious?

Bladder wall thickening can happen for many reasons — not just cancer. Infections, inflammation, or even aging can cause it. It’s good that you’re following up with your doctor. Try not to worry too much until more tests are done — most cases turn out to be treatable and not serious.

I’ve been having frequent urination and mild pelvic discomfort. Could that be related to bladder wall thickening, or is it likely something else?

Frequent urination and pelvic discomfort can indeed be related to bladder wall thickening, but they can also result from other conditions like infections, overactive bladder, or interstitial cystitis. It’s important to get a proper evaluation, including a urine test and possibly imaging. Don’t worry — many of these issues are manageable with the right treatment.