Anemia, a condition characterized by a deficiency in red blood cells or hemoglobin, impacts millions worldwide, manifesting as fatigue, weakness, shortness of breath, and pale skin. Diagnosing anemia typically involves a comprehensive evaluation that includes a complete blood count (CBC) – the gold standard for identifying this condition. However, beyond the CBC, many individuals wonder if simpler tests like urinalysis can offer clues about their iron levels or overall red blood cell health. While urinalysis isn’t a primary diagnostic tool for anemia itself, it can reveal indirect indicators that suggest an underlying issue prompting further investigation and potentially supporting an anemia diagnosis when used in conjunction with other tests. Understanding the nuanced relationship between urine analysis and anemia requires exploring what urinalysis detects, how those findings relate to different types of anemia, and its limitations as a diagnostic method.

Urinalysis is routinely performed for various reasons – from routine health checkups to diagnosing urinary tract infections or kidney problems. It doesn’t directly measure hemoglobin levels like a CBC does. Instead, it examines the physical, chemical, and microscopic components of urine. These components can sometimes offer clues about systemic conditions impacting the body, including those that influence red blood cell production and breakdown. For example, detecting blood in the urine (hematuria) could signal several issues – kidney disease, infection, or even certain types of anemia leading to increased red blood cell destruction. It’s crucial to remember that hematuria isn’t exclusive to anemia; it has a vast range of potential causes, making accurate interpretation vital and necessitating further diagnostic steps. The role of urinalysis in the context of anemia is therefore not about definitive diagnosis but rather about providing supplemental information or raising suspicion for more targeted testing.

Understanding Hematuria & Its Connection to Anemia

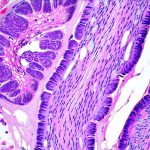

Hematuria, or blood in the urine, is perhaps the most relevant finding in a urinalysis that might raise concerns related to anemia. It’s categorized as either microscopic (detectable only under a microscope) or macroscopic (visible to the naked eye). The presence of blood doesn’t automatically indicate anemia but warrants investigation because certain anemias can cause hematuria indirectly. For example, hemolytic anemia – where red blood cells are destroyed at an accelerated rate – can lead to hemoglobinuria (hemoglobin in urine), which may appear as reddish or brownish discoloration and could be detected during urinalysis. – Hemoglobinuria occurs when the kidneys filter out excessive amounts of free hemoglobin released from broken-down red blood cells.

However, it’s vital to emphasize that hematuria has many more common causes than anemia. These include urinary tract infections (UTIs), kidney stones, bladder cancer, and even strenuous exercise. Therefore, a positive result for blood in the urine necessitates further investigation to determine the source of the bleeding before considering anemia as a potential cause. Further tests like imaging scans (CT or MRI) and cystoscopy might be needed to pinpoint the origin of hematuria and rule out other more likely explanations. The urinalysis is essentially acting as an initial screening tool, prompting clinicians to look deeper when blood is detected.

Urinalysis & Kidney Function in Anemia

Anemia can sometimes impact kidney function, and conversely, kidney disease is a frequent cause of anemia. This bidirectional relationship makes assessing kidney health through urinalysis relevant when investigating potential anemia. Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD) often leads to decreased production of erythropoietin, a hormone essential for red blood cell production, resulting in renal anemia. Urinalysis can detect protein in the urine (proteinuria), which is an early sign of kidney damage and CKD. – Proteinuria indicates that the kidneys are not effectively filtering waste products from the blood.

Additionally, urinalysis assesses the levels of creatinine and urea nitrogen, waste products cleared by the kidneys. Elevated levels suggest impaired kidney function, further supporting the possibility of renal anemia. However, it’s important to note that proteinuria can occur in other conditions besides CKD – like diabetes or high blood pressure – making a comprehensive evaluation essential for accurate diagnosis. The combination of urinalysis findings with blood tests measuring kidney function (BUN and creatinine) provides a more complete picture of the patient’s renal health and its potential role in anemia development.

Detecting Hemoglobinuria & Myoglobinuria

Hemoglobinuria, as mentioned earlier, is the presence of hemoglobin in the urine due to hemolysis – the breakdown of red blood cells. It’s relatively rare but can be detected through urinalysis. However, distinguishing between hemoglobinuria and myoglobinuria (myoglobin in the urine from muscle damage) can be challenging with a standard urinalysis test. – Myoglobin is a protein found in muscle tissue.

A confirmatory test called a heme test can help differentiate between the two because it specifically identifies heme, the iron-containing component of hemoglobin. Myoglobinuria often occurs after intense exercise or trauma causing rhabdomyolysis (muscle breakdown), while hemoglobinuria typically points to hemolytic anemia or transfusion reactions. A positive result for either necessitates further investigation into the underlying cause – identifying the type of hemolysis in case of hemoglobinuria, or assessing muscle damage and kidney function in cases of myoglobinuria.

Assessing Urine Specific Gravity & Hydration

Urine specific gravity measures the concentration of solutes in urine, reflecting hydration status and kidney function. While not directly related to anemia diagnosis, it’s important because dehydration can falsely elevate some blood test results used to assess anemia (like hematocrit). – A dehydrated state concentrates the blood, potentially giving a misleadingly high reading for red blood cell count.

Therefore, assessing urine specific gravity helps ensure accurate interpretation of CBC results. Additionally, in certain anemias like sickle cell anemia, maintaining adequate hydration is crucial to prevent vaso-occlusive crises (blockage of small blood vessels). Monitoring urine specific gravity can help clinicians assess a patient’s fluid balance and encourage sufficient hydration. A low specific gravity suggests overhydration, while a high one indicates dehydration or concentrated urine due to kidney issues.

Limitations & The Importance of Comprehensive Testing

Despite its potential for providing supporting information, urinalysis has significant limitations in diagnosing anemia. It cannot directly measure hemoglobin levels, iron stores, or red blood cell indices – the key parameters assessed by a CBC. A normal urinalysis does not rule out anemia; many individuals with anemia will have completely normal urine tests. Furthermore, false positives and false negatives can occur due to various factors like contamination, medication use, or improper collection techniques.

The cornerstone of anemia diagnosis remains the complete blood count (CBC), which provides detailed information about red blood cell size, shape, hemoglobin content, and overall number. Other essential tests include iron studies (serum iron, ferritin, transferrin saturation), vitamin B12 and folate levels, and potentially bone marrow aspiration in complex cases. Urinalysis should be considered an adjunct to these core diagnostic tests – a piece of the puzzle that might raise concerns or provide additional clues but never a substitute for comprehensive evaluation by a healthcare professional. Relying solely on urinalysis results can lead to misdiagnosis or delayed treatment, highlighting the importance of a thorough medical assessment and accurate interpretation of all relevant test findings.