Bladder Pain Syndrome (BPS), also frequently referred to as Interstitial Cystitis/Bladder Pain Syndrome (IC/BPS) represents a complex and often debilitating condition characterized by chronic pelvic pain, urinary frequency, and urgency. It impacts millions worldwide, profoundly affecting quality of life. The etiology remains incompletely understood; it’s believed to be multifactorial, involving neuroinflammation, epithelial dysfunction, and potentially autoimmune processes. Diagnosis is challenging due to overlapping symptoms with other conditions like urinary tract infections, overactive bladder, and pelvic floor dysfunction. Therefore, a thorough evaluation and careful consideration of the patient’s history are crucial for accurate identification and appropriate management strategies.

The treatment approach to BPS is typically multimodal, aiming to manage symptoms rather than cure the underlying condition. This frequently involves lifestyle modifications – such as dietary adjustments (avoiding bladder irritants like caffeine, alcohol, citrus fruits), stress reduction techniques, physical therapy focusing on pelvic floor rehabilitation, and various pharmacological interventions. While there’s no single “magic bullet,” modern antispasmodics play a significant role in alleviating the urinary frequency, urgency, and associated pain experienced by many BPS sufferers. Understanding their mechanisms, limitations, and evolving applications is essential for effective patient care. The goal isn’t just symptom suppression, but rather improving functionality and overall well-being.

Modern Antispasmodics: Mechanisms & Traditional Options

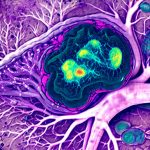

Antispasmodics work primarily by reducing involuntary contractions of the detrusor muscle – the smooth muscle in the bladder wall responsible for emptying. In BPS, this muscle can become hyperactive, leading to frequent and urgent urination even with small amounts of urine present. Traditionally, antispasmodics have fallen into a few key categories. Oxybutynin was among the first widely used options, functioning as an anticholinergic – blocking acetylcholine receptors in the bladder. This reduces detrusor muscle contractility. However, oxybutynin and similar drugs like tolterodine are associated with significant anticholinergic side effects such as dry mouth, constipation, blurred vision, and cognitive impairment, especially in older adults. These side effects frequently limit adherence to treatment.

More recent developments have focused on minimizing these adverse effects while maintaining efficacy. Solifenacin and darifenacin are examples of selective M3 receptor antagonists. The M3 receptor is the primary subtype responsible for detrusor muscle contraction, so targeting it selectively reduces bladder activity with fewer off-target anticholinergic effects. This results in a better tolerability profile compared to older agents, though some side effects still occur. Furthermore, research suggests that BPS isn’t solely about detrusor hyperactivity; neuroinflammation and nerve sensitization play critical roles. Therefore, antispasmodics are often used in conjunction with other therapies addressing these aspects of the condition.

The choice of antispasmodic isn’t one-size-fits-all. Factors such as patient age, comorbidities, symptom severity, and previous responses to treatment all influence selection. It’s vital to initiate therapy at a low dose and titrate upwards gradually based on response and tolerance. Regularly monitoring for side effects is also crucial. Beyond pharmacological interventions, behavioral therapies like bladder retraining are often recommended alongside antispasmodics to help patients regain control over their urinary function.

Emerging Antispasmodic Approaches

The limitations of traditional antispasmodics have spurred research into novel approaches targeting different mechanisms involved in BPS pathogenesis. One area of investigation focuses on beta-3 adrenergic agonists. Mirabegron, for example, activates beta-3 receptors in the bladder, causing detrusor muscle relaxation without relying on anticholinergic pathways. This offers a potentially better side effect profile compared to traditional antispasmodics, particularly regarding cognitive function and dry mouth. While mirabegron is approved for overactive bladder, its use in BPS is increasing as clinicians seek alternatives with improved tolerability.

Another promising avenue involves modulating neuronal pathways involved in pain perception. OnabotulinumtoxinA (Botox) injections into the bladder wall have demonstrated efficacy in reducing urinary frequency and urgency in some BPS patients. Botox works by temporarily paralyzing the detrusor muscle, decreasing its contractility. However, it requires repeated injections every 6-9 months, and there’s a risk of urinary retention or incomplete emptying. This makes it more suitable for carefully selected patients who haven’t responded to other therapies.

Finally, research is exploring the role of neuroprotective agents and drugs targeting neuroinflammation in BPS. Pentosan polysulfate sodium (Elmiron) was historically used as an oral treatment option, though its use has declined due to concerns about potential retinal toxicity. Newer compounds aiming to reduce inflammation and nerve sensitization are under development, offering hope for more targeted therapies that address the underlying causes of BPS pain.

The Role of Combination Therapy

The complexity of BPS often necessitates a combined approach to management. Antispasmodics rarely provide complete relief on their own; they’re most effective when integrated into a comprehensive treatment plan. This might include: – Pelvic floor physical therapy: Strengthening and relaxing the pelvic floor muscles can improve bladder control and reduce pain. – Bladder retraining: Gradually increasing the time between voiding intervals can help restore normal bladder capacity. – Dietary modification: Identifying and eliminating bladder irritants can minimize symptom flare-ups. – Pain management techniques: Addressing chronic pain with modalities like nerve blocks, trigger point injections, or medications beyond antispasmodics.

Combining different types of antispasmodics is generally not recommended due to the increased risk of side effects without necessarily providing greater benefit. However, combining an antispasmodic with a non-pharmacological approach – such as bladder retraining and pelvic floor therapy – can be highly effective. For example, a patient might take solifenacin to reduce urinary frequency while simultaneously working with a physical therapist to strengthen their pelvic floor muscles. This synergistic effect addresses both the physiological and functional aspects of BPS.

Personalized treatment is paramount. Each patient’s response to therapy varies considerably. Careful monitoring, open communication between the patient and healthcare provider, and willingness to adjust the treatment plan are essential for optimizing outcomes. It’s important to remember that managing BPS is often a long-term process requiring patience and collaboration.

Future Directions & Research Needs

Despite advancements in understanding and treating BPS, significant research gaps remain. One key area of focus is identifying biomarkers that can help diagnose the condition earlier and predict treatment response. Currently, diagnosis relies heavily on symptom assessment and exclusion of other conditions. Discovering objective markers would greatly improve diagnostic accuracy and streamline patient care. Furthermore, a deeper understanding of the neuroinflammatory processes driving BPS pain is needed to develop more targeted therapies.

Research into novel drug delivery systems could also enhance the effectiveness of existing antispasmodics. For example, localized bladder injections or sustained-release formulations might minimize systemic side effects while maximizing therapeutic benefits. Clinical trials are ongoing to evaluate the efficacy of new compounds targeting different pathways involved in BPS pathogenesis, including those modulating neuroinflammation and nerve growth factor signaling.

Ultimately, a more holistic approach is needed. This involves integrating pharmacological interventions with behavioral therapies, lifestyle modifications, and psychological support. Addressing the emotional burden associated with chronic pain is crucial for improving quality of life. Future research should also focus on developing personalized treatment plans tailored to each patient’s unique characteristics and preferences, moving beyond a “one-size-fits-all” approach. Continued investigation and collaboration are essential to improve the lives of individuals living with this challenging condition.